Coming of Age in Gaza before the Genocide

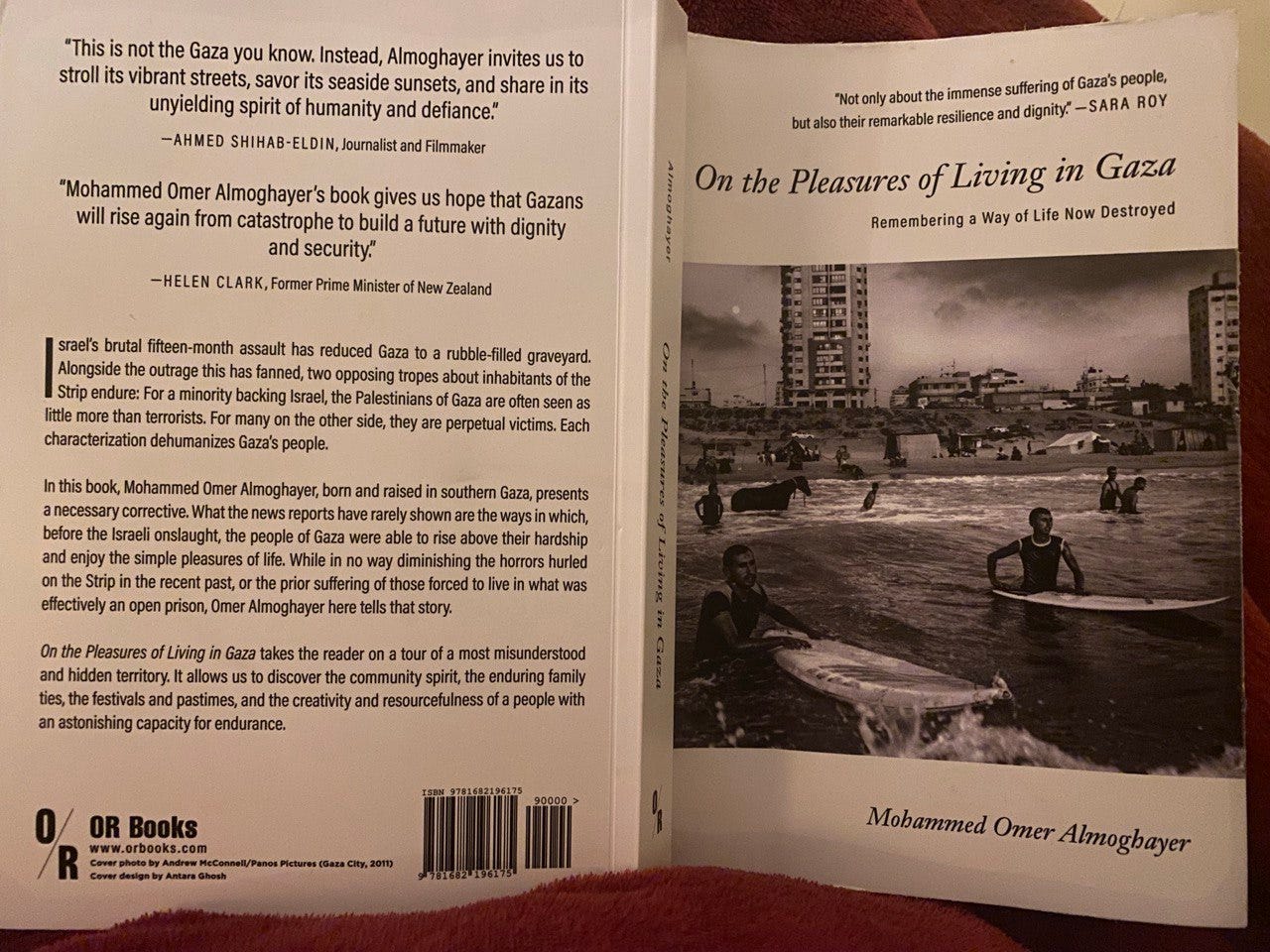

Mohammed Omer Almoghayer's On the Pleasures of Living in Gaza

Dear Readers,

Welcome to the 8th edition of The Textual Materialist newsletter, where we examine the intersection between politics and poetics, two realms of experience that need each other.

In my last newsletter, I promised a part II for the newsletter “To What Shall We Compare Gaza?” that would be a continuation of the scholarly article from which that is excerpted. I have decided to leave that for later for a few reasons.

First, I have in the interim gained a number of new subscribers (welcome!) who might be more interested in short(er) form work. Second, the book which I introduce below has only just been published in the US and is now scheduled for imminent release in the UK, so I wanted to bring it to your attention as soon as possible and urge you to buy it (or preorder it if you are in the UK).

Third, I am proud of the long version of “To What Shall We Compare Gaza? and hope it makes a long term contribution to our understanding of racism (including antisemitism) but it is dense, philosophical, and gets deep into the weeds of legal jurisprudence, especially in part II. So I expect it may only appeal to the scholarly-inclined among you. I do write for scholars, but not only for scholars, and this particular issue of the newsletter is for a wider audience.

As for the book discussed below, I was so excited about it that I did a voiceover for my review. I hope it is useful for some of you and please don’t judge my voice too harshly, as it is my first time! By way of illustrating the world evoked in Almoghayer’s book, I am honored to include some photos that a dear friend in Gaza took for me in April 2024, before Rafah was completely destroyed.

By the time you receive this, I will be in Egypt, conducting research and meeting with Palestinians who were forced to flee Gaza early in the genocide. In light of all the horrors that we have been witnessing, it is particularly important to remember the amazingly beautiful place Gaza always was and always will be, as part of a free Palestine. Books like Mohammed Omer Almoghayer’s which I discuss below remind us of that vital reality.

Finally, as I experiment with the many tools that Substack has to offer I would like to try one with you, a poll. I have started working on an article entitled “Weaponizing Palestine: On the Fractures in Pro-Palestine Solidarity Across the Global Iranian Diaspora.” The title speaks for itself.

For the past few years I have been preoccupied (pun intended) with Palestine but my PhD dissertation and much of my life has focused on Persian poetics. So, naturally, I have thoughts about Iran’s engagement with Palestine. I am mostly interested not in what the Islamic Republic of Iran has to say on the matter but on the thoughts of the Iranian people.

Anyone who knows anything about Iran today knows the challenges and potential conflicts (including interpersonal ones!) that this issue brings. Hence, I would love to gauge your opinions on the matter of Palestine solidarity from an Iranian perspective. (And if you are not Iranian, as most of you are not, that’s fine; I am simply seeking the views of everyday people, not states.) Note that I ask here about the people of Iran and Palestine, and not their governments. If you have any further thoughts on the matter feel free to say so in the comments.

Sending my solidarity with all your struggles and efforts to make the world a better place, wherever you are on this earth,

Rebecca

Addendum, now that I’m getting the hang of polls, I’d be very grateful if you could also answer this question for me, which will help me determine what I post here, avoid duplicate content, and tailor my material to your interests:

Coming of Age in Gaza before Genocide: Mohammed Omer Almoghayer’s On the Pleasures of Living in Gaza

When he embarked on writing On the Pleasures of Living in Gaza, his newly-published mosaic of life in Gaza before the genocide, Palestinian writer and journalist Mohammed Omer Almoghayer decided that he would narrate the stories he had to tell in the present tense.

By recasting events from the past as if they were happening in the present, Almoghayer makes “Gaza feel alive once more,” in his own words. The Gaza that comes to life in Almoghayer’s book is “an illusion, a resurrection, a magic spell.”

Gaza is also his home, the place where he was born and raised, where he came to know the fascinating cast of characters who comprise his book, and where he was first introduced to a people who understood that life at its best is not about material success or dominance over others.

Almoghayer’s book is in part a memoir of his coming of age in Gaza. Yet, as a memoir it is unique in that it is mostly about people other than himself. As I immersed myself in Almoghayer’s chronicle of the chefs, the teachers, the surfers, and the fashion designers of Gaza, I was reminded of the thrill of discovering African-American poet Langston Hughes’s journey through Central Asia in Wonder as I Wander (1956).

Like Hughes, Almoghayer has a gift for capturing how people learn to love life under the most difficult of circumstances. The roots of this book are however first and foremost in Palestinian literature. On the Pleasures of Living in Gaza joins with other accounts of growing up in Gaza after the Nakba, such as the memoirs of Muin Bseiso and political prisoner Nasser Abu Srour, while charting a path all its own.

Despite the French having coined the term joie de vivre (joy in living), it is Gazans who have perfected the art of living on Almoghayer’s account. They know to make do with little, and even to thrive. Without romanticizing his people, Almoghayer reminds us that there always has been and there always will be more to life in Gaza than genocide.

While acknowledging the hardships imposed by the perpetual electricity cuts that marked life in Gaza before the genocide, Almoghayer notes that they “force families to rely on each other for entertainment and social connection as they gather in the evening to chat on doorsteps and in courtyards.”

Similarly, Almoghayer’s account of how disabled people are cared for and honoured as full members of Gazan society could serve as a lesson for any society anywhere in the world. In Gaza, Almoghayer explains, “people with disabilities are supported and understood in ways that are often hard to come by elsewhere.”

The major difference between the status of those with restricted mobility and elsewhere is that in Gaza, the disabled “don’t have to fight for access, inclusion, or representation because everyone has sympathy for people whose bodies have been dismembered by Israel’s military.” A world in which “disability has become normalized” (as Almoghayer puts it) is one that is more equal, more inclusive, and more caring for the entire community.

Almoghayer does not idealize the struggle of the Palestinian people against the slow genocide that was already underway before 7 October 2023. Nor does he, like many western commentators far removed from this struggle, rely on the “resilience” of the Palestinian people as if that could make genocide acceptable.

Palestinian scholar Malaka Shwaikh shows how the resilience framework is often used as a political tool by global development organizations “to pass the burden of coping with violence to individuals instead of tackling the root causes of (structural) violence.” By contrast, Almoghayer gives us a fully textured portrait of the people who have shaped his sense of self and awakened him to what it means to be human.

Some reviewers found Almoghayer’s account to be unpersuasive. I found Almoghayer’s portraits convincing, perhaps because I know Palestinians who are as brave and kind-hearted as those he describes. One of them kindly took the photos which I share here.

Among the many people whose stories he tells, readers will always remember Hassan, who owns and manages a specialist medical lab in Rafah’s city centre. As the person who administers and interprets medical tests for the people of Rafah, Hassan is at the center of his community. He counsels a pregnant teenager and helps her to deal with the consequences of an unexpected pregnancy. In another subplot, Hassan assists a couple dealing with infertility and persuades the husband that it is he rather than his wife whose medical issues are preventing them from conceiving a child.

Almoghayer’s storytelling is non-linear. The story of Naji, whose life was changed for the better after a photograph depicting his abuse by an Israeli soldier was published and reached a wider audience, is interspersed throughout the book in a series of “interludes.” The non-linear presentation of Naji’s story adds to the suspense as we move through the narrative.

Many of Almoghayer’s most moving stories center on relationships that people in Gaza have established with the outside world. From Italian chefs to foreign diplomats to Banksy, Almoghayer shows how, despite the towering security walls, the buffer zones, and the checkpoints, Gaza is connected to the rest of the world.

Thanks to the internet, Gazans have formed deep friendships with supporters around the world who have been unable to enter Gaza. Physical distance and impenetrable borders have not prevented lives from being changed for the better through friendship, solidarity, and mutual learning.

Almoghayer has an extraordinary eye for detail. The experience of reading the book involves all the senses: sight, taste, touch, smell, and hearing. He takes particular delight in describing the culinary range of Gazan food. From maqlouba to kunafeh, the fresh vegetables, fruits, and spices of this fertile land contribute to a cuisine that is uniquely savoury and sweet.

We smell “ground wheat still mingling with the rich aroma of freshly ground and brewed coffee” and savour the delicacy of the stuffed grape leaves (waraq enab) made by his grandmother. Beyond food, we witness the cresting waves of the Mediterranean Sea as they crash on Gaza’s shores, and the beauty of Gaza’s nighttime skies when they are not filled with drones.

For those of us who are frustrated with waiting for our protests to stop the genocide, Almoghayer provides insight into what solidarity means for the people of Gaza. He acknowledges that “people in Gaza often feel overwhelmed and isolated” but adds that “support and solidarity from friends around the world […] make a real difference in their ability to cope and recover and feel enough space in their psyche to hope and dream of a better future.” There is a place for everyone in Almoghayer’s book, including the reader.

On the Pleasures of Living in Gaza is as hopeful a book as could have been written in a time of genocide. In the final chapters, Almoghayer confronts this genocide directly, and considers all that has been lost. He also recounts his own experience of being taken captive by a shadowy group aligned to the Islamic State.

Alongside the author, credit should also be given to the publisher for bringing this book into the world, and for their stellar list of titles relating to Palestine, including the collected works of the martyred poet and educator Refaat Alareer, which deservedly became one of the top 100 world bestsellers following its publication in December 2024.

To conclude, this book provides a broader context for the accounts of starvation and mutilation that emerge from Gaza today. Far from negating the horror of life in Gaza that is enfolding in front of our eyes, Almoghayer gives us a framework for appreciating all that has been destroyed and for honoring the brilliant artists, creators, mothers, fathers, and children who have been martyred.

Taking Almoghayer’s world seriously means working towards the time when Gaza will be reborn, like the phoenix that regenerates itself. It was after this phoenix that the Municipality of Gaza’s reconstruction plan—still the best proposal for bringing peace to Gaza—was named.

Thank you so much Dr. Gould for your profound, insightful and enlightening review. Indeed you did the book a great justice, and I think your review just added value and beauty to it.

I was born, raised and still live in the same streets,refugee camps and cities

Almoghayer mentioned in his book. I know the characters he chose to write about, I know them closely and in person. and I confidently say that he managed to portray them perfectly.

He has skillfully articulated Gaza as I knew before the genocide and I think he managed to assure readers that Gaza will maintain the spirit she always had.

We, Gazans know that She will resurrect and restore her eternal beauty.

Thank you again Dr. Ruth, with your review you have breathed more soul into the book.

I love the photos you selected for your article, they resonate deeply with me, appreciated.

Thankyou for this beautiful reminder of the peace of Gaza, unimaginable now to most of us on the outside, but real as memory and, we hope, a reality to return.